New research suggests that politicians systematically misperceive constituent perspectives on a range of issues. Lawmakers and their legislative priorities are remarkably unpopular with the public as a result. How can politicians and government organizations better understand and represent citizen perspectives?

US government institutions often have difficulty connecting with the citizenry that they serve. Sometimes this is because the organization’s work is very technical: asteroid exploration options, for instance, aren’t frequently the subject of informed public discussion. Sometimes the work is controversial, as when considering funding climate engineering research. Sometimes it’s both: managing the country’s nuclear waste has been the subject of highly contentious debate for decades.

At the Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes (CSPO), we have worked with agencies such as NASA, the Department of Energy, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to make some of their programs more responsive to public values. While experts and motivated stakeholders play large roles in public policies, citizen perspectives are a critical but often overlooked input for decisions related to science and technology. These decisions can have a profound effect on the public, ranging from how taxpayer dollars are spent to the manifold ways emerging technologies shape—and are shaped by—society.

In partnership with a number of other organizations, we have developed ways to solicit and analyze public perspectives. Premised on the assumption that these perspectives are vital inputs for even highly technical decisions, participatory technology assessment substantively engages citizens on a variety of scientific and technological issues. We bring together trusted institutions—academic researchers, science museums, and nonpartisan think tanks—to provide information to and facilitate deliberation among diverse groups of citizens.

These public deliberations provide detailed, nuanced information about everyday people’s perspectives on a subject. We learn about their values, their reasoning, and how their viewpoints developed. Our method focuses on the rich content of people’s conversations, written rationales, and personal testimonies to map out the complex ways that citizen perspectives can inform and shape decisions about important scientific and technological issues.

For example, when exploring various options for NASA’s Asteroid Initiative, citizen participants were able to incorporate complicated technical concepts into their deliberations. The perspectives they shared on various missions’ costs, benefits, and risks were therefore well informed and useful to NASA engineers and scientists. The space agency learned that citizens had little interest in the idea of “asteroid mining” and placed much greater value on using the technical capabilities developed through the Asteroid Initiative to improve planetary defenses in the case of a potential asteroid impact. NASA adjusted its messaging accordingly.

Although our work focuses on emerging technologies and scientific research, there is no reason the method cannot be applied other issues of broad public concern. The current political landscape provides overwhelming evidence that a better understanding of citizens’ perspectives is needed.

Since the Republican party took control of both houses of Congress in 2015, much of the legislative agenda has been remarkably unpopular with the American public. Repealing Obamacare without a coherent replacement plan, a top priority for President Trump and Republican lawmakers, did not have the support of a majority of voters. The only significant congressional legislation of the year, the tax bill that Republicans passed along party lines at the end of 2017, was never popular with much more than a third of the electorate.

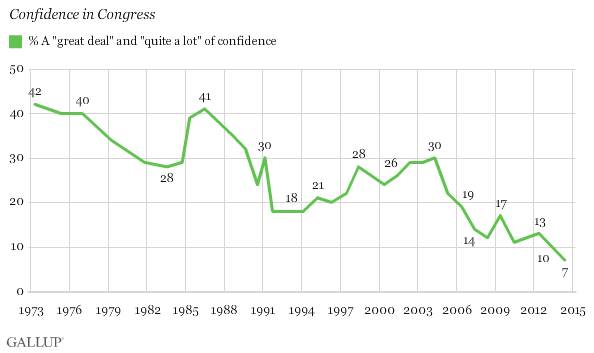

At the same time, Republican lawmakers seem to ignore or vote against bills that a majority of the public appear to support, such as basic gun control laws, reform of the immigration system, or climate change policies. By rarely working on bipartisan legislation that most citizens favor and instead adopting broadly unpopular and ideologically extreme policy positions, politicians of both parties—but especially conservatives, at the moment—contribute to the idea that the legislative branch is hopelessly polarized and gridlocked. This is reflected in abysmal congressional approval ratings.

A number of different factors likely account for the polarized legislative environment. Many incumbents in districts that have been made “safe” through gerrymandering mainly have to worry about losing a primary election to a more ideologically extreme opponent; adopting ideologically pure positions counters this threat. Partisan media outlets and institutions energize base voters and generally oppose compromise on issues important to their audiences or funders. Political donors with extreme ideological views can have an outsize influence on politicians’ positions.

A forthcoming study in the American Political Science Review by David E. Broockman and Christopher Skovron suggests an additional reason that unpopular partisan legislation is adopted while popular moderate policies are ignored: political elites are simply misinformed about their constituents’ perspectives. They find that “politicians can systematically misperceive what their constituents want.”

This misperception, which the authors characterize as “large, pervasive, and robust,” generally leads legislators of both parties to believe that the people they represent hold far more conservative opinions than they actually do. The factors noted above—gerrymandering, partisan media and institutions, and donors—only strengthen the perception that the American public is very conservative on issues such as gun control, same-sex marriage, and immigration.

Because lawmakers are influenced by their constituents’ opinions to some degree (they are elected, after all), politicians then tend to adopt more conservative positions than they otherwise would. Interestingly, politicians of both parties appear to hold this misperception of conservativeness on the part of their constituents, meaning that Democratic politicians underestimate support for liberal positions while Republicans overestimate support for conservative policies. The political feasibility of left-leaning policies—no matter which party controls Congress or the presidency—thus shrinks dramatically.

Legislators have a variety of ways to gauge public opinion on a topic. But, as any issue advocate is well aware, one of the most effective methods of influencing a politician is to actively engage with him or her: call the representative’s office, speak up at town hall meetings, and write letters and emails. Broockman and Skovron attribute conservative misperception to precisely this kind of grassroots activism: “actors on the political right built the capacity to ‘rapidly organize large numbers’ of conservative citizens to participate in the public spheres representatives monitor.”

But Broockman and Skovron’s study is limited to 2012 and 2014. With the liberal grassroots energized by the election of Donald Trump, the political elite may now—or soon—believe that their constituencies are far more liberal than they actually are, skewing lawmakers’ policy preferences in the opposite direction. While the citizen activism that Broockman and Skovron describe is democratically healthy and useful for politicians to judge the intensity of feeling around an issue, the systematic misperception that results from it—and the consequent lack of political compromise, bipartisanship, and imagination—makes for very poor policymaking.

One way to address the misperception problem is to improve the kind of information lawmakers receive about their constituents’ views. There are, of course, public opinion surveys and focus groups, both of which are used by politicians and have their own benefits and drawbacks. But through CSPO’s work with federal agencies, we have found that substantive public engagement in the form of citizen deliberations and other tools can provide insight into public values. These values run deeper than people’s day-to-day opinions on controversial subjects and are more broadly representative than small focus group preferences. Policy decisions informed by these values may be more robust and socially responsible.

If we are able to collaborate with organizations to explore nuanced citizen perspectives on complex technical questions, this form of engagement should be well suited to other topics too. Gaining a better understanding of constituent perspectives, especially on hot-button issues such as climate change, gun control, reproductive rights, and immigration, can help lawmakers better represent the people who elected them. It can also, perhaps, expand the possibilities of political action for tackling some of the major policy challenges facing the country.