For three decades, the US has looked at carbon emissions as if they wereThe Little Engine That Couldn’t.” The problem was basically too big a mountain to try to cross. Science magazine reported in 1997, as the world was negotiating the Kyoto Protocol: “Current projections put U.S. emissions at 13% above 1990 levels by the end of the decade, with continued increases for the foreseeable future.” Even ardent proponents of action to address global warming—myself included—felt stymied by the shear scope of required changes. US emissions seemed on an inexorable path upward, barring actions that would create enormous negative impacts. Such actions would only come through political and economic leadership, and absent such leadership there was little motivation to undertake individual change. It was the opposite of a free rider problem. Why incur economic cost yourself when it seemed clear no one else would act with you? The larger dialogue in Washington, DC—why should the US act, if nations link China weren’t planning to—was simply a reflection of our own personal logic of inaction.

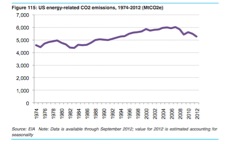

Yet, unknown to just about anyone, the US has overturned this logic. Over the past five years, the US has accomplished a feat no one thought possible. Instead of ever increasing carbon emissions, the US is now actually reducing its carbon emissions. In fact, while we won’t meet Kyoto Protocol targets, the US is already back down to 1994 levels and poised to go lower. This is, in part, due to the recession, in part, due to a shift from coal to natural gas, and in part due to efficiency gains throughout the economy. But why we’ve turned the corner isn’t nearly as important as the simple fact that we have. This new fact positions us to fundamentally transform the politics of carbon in the United States. We are now The Little Engine That Could.

The power of despair in shaping US climate politics is evident in Yale’s Six America’s study:

Few Americans are confident that humans will successfully reduce global warming – six percent or less in each of the six groups. Majorities of the Alarmed, Concerned, Cautious and Disengaged say that humans are capable of reducing global warming, but that it’s unclear at this point whether we will do what’s needed. By contrast, 98 percent of the Dismissive and two-thirds of the Doubtful (65%) say that humans aren’t able to reduce global warming, or that it is not happening. Between 20 and 27 percent of all the groups except the Dismissive believe that humans could reduce global warming, but are not going to do so because people aren’t willing to change their behavior.

Here is the crux of the problem. If you don’t believe a problem will be solved, there’s little motivation to even try. But declining carbon emissions in the US fundamentally changes the psychology of the problem. Now that emissions are declining, every new effort to reduce carbon emissions—no matter how small—accelerates the curve downward. Under these conditions, every little bit helps, creating positive motivation for people to act. This is, put simply, the psychology of tipping points. Once people see that their actions do matter, they can become powerfully stimulated to act.

So what is it that will move people from motivation to action? The answer will be social networks. I’m willing to bet that the US has reached peak carbon. I could be wrong, of course. Many people believe this is simply a temporary effect of the recession and cheap natural gas. But there’s no reason why we can’t, as a society, continue on the path to lowering carbon emissions. Let’s just chug along. If we think we can, maybe we actually can. Social networks could be a powerful tool, if mobilized, for helping everyone to get involved in taking action.

We’re already seeing the effect in Arizona. In some Arizona communities, even some very conservative communities, more than 10% of the rooftops have solar panels on them. Why? Social networks operate in those communities that spread knowledge and insights, foster trust, mitigate transaction costs, and promote healthy social competition. People know that solar panels are good for the environment, but that’s not why they put them on their roof. Rather, they get to brag to their neighbors or their golf partners how much they’re saving on their electricity cost. They learn about the benefits from people they trust, and they get references on good solar companies to work with. There’s nothing liking making a major investment and feeling like you’re out on a limb on your own. But if your friends and neighbors have already done it, it gets a lot easier.

What we need is a social acceleration of carbon reduction. People need to see that US emissions are not on an ever-upward path and that, therefore, climate change can be solved. If they do, they will be motivated to take action. They will see that they are part of the solution. “I think I can. I think I can. I think I can. I think I can.” Right on down the mountain.

This is a unique opportunity. If we let emissions climb again, it will be just that much harder to get them down again. Now is the time.

· Take your utility up on their offer to let you buy electricity from solar or wind farms, even if it costs a little more. You won’t just be pissing away money any more. You’ll be buying down America’s carbon debt.

· Put solar panels on your roof—or on the roof of your business. Even if you can’t quite break, you’ll be buying down the cost of future solar panels for your neighbor.

· Brag about your solar panels. Your neighbors will be jealous and buy their own.

· Reward businesses with solar panels on their roof by buying stuff from them. If you can’t see the roof from the ground, check them out on Google Maps. Tell your neighbors which businesses have installed solar.

· Encourage your boss to install solar. It’s good business.

· The next time you buy an electric furnace or air conditioner, buy the highest efficiency one you can afford. You’ll save money in the long run, cut your carbon emissions, and incentivize manufacturers to make even more efficient ones in the future.

· The next time you buy a car, buy one that gets better gas mileage. Brag about how rarely you have to fill up.

· Ride a bike to work. It’s good for your heart.

· Vote for candidates who are willing to take action.

“I think I can. I think I can.”

Clark Miller is the associate director for the Consortium for Science, Policy and Outcomes at Arizona State University. Follow him on Twitter: @ClarkAMiller.